How to Protect Yourself and Others from Extreme Indoor Heat

Dr. Sarah Henderson shares the risks of extreme heat indoors and how people can protect themselves and others.

by ecobee on 09/07/2022 in Experts

14 min read

More than 200,000 ecobee Smart Owners have opted-in to ecobee’s one-of-a-kind Donate Your Data program, creating a unique window into energy use in the home, and making it the world’s largest home energy efficiency dataset. By sharing the anonymized data from customers who have opted in, ecobee is helping researchers around the globe in their studies aimed at creating a more sustainable and healthier future for communities.

“A big part of our impetus for starting ecobee was to transform scientific research and make breakthroughs possible,” said Stuart Lombard, ecobee founder and CEO.

“At that time [2007], energy efficiency studies were limited to a handful of homes because the cost to equip homes with the proper instruments was prohibitive.”

Following through on Stuart’s vision, the team launched Donate Your Data in 2017.

Today, a prominent scientist using this data is Dr. Sarah Henderson, Scientific Director for Environmental Health at British Columbia Centre for Disease Control (BC CDC). We sat down with Dr. Henderson to discuss the results of an important study with real-world implications and the ways that communities around the world can manage extreme heat.

ecobee Citizen: What is your field of study?

Dr. Henderson: I'm the scientific director of Environmental Health Services at the BC CDC, and I'm an environmental epidemiologist by training. My field of study is how the environment affects human health. A lot of my work is related to extreme temperatures and the population health effects of heat exposure. I have expertise in a wide range of subject matter, but the reason we’re so interested in the data from the ecobee Donate Your Data program is because of the work that we do when it gets very hot outside.

ecobee Citizen: How did you hear about the Donate Your Data program?

Dr. Henderson: Western North America, and especially British Columbia, experienced an extreme hot weather event in 2021. It was one of the most intense heat domes ever recorded on the face of the planet; we had temperatures that were 15 to 25°C above seasonal norms in the region and over 600 people died as a result.

Heat can accumulate indoors, especially in environments where windows are facing the sun, or in units on the top floor of multi-unit residential buildings. These homes can get very hot, and it can even get hotter inside than it is outside.

After this event last year, I was looking for information on how hot indoor temperatures got in some environments and that information is quite challenging to find. We have weather stations all over Canada that measure outdoor temperatures, but accessing information on indoor temperatures is harder.

I was writing to friends of mine who work at Google and Amazon because I know that smart thermostats must record this information, but they couldn’t share their data with me. Then someone suggested that I should check out ecobee. They told me it was a Canadian company with a Donate Your Data program that could probably help get me some of the information we were looking for.

What the climate is telling us is that this is life now, and we need to adapt.

ecobee Citizen: How did you use the data set?

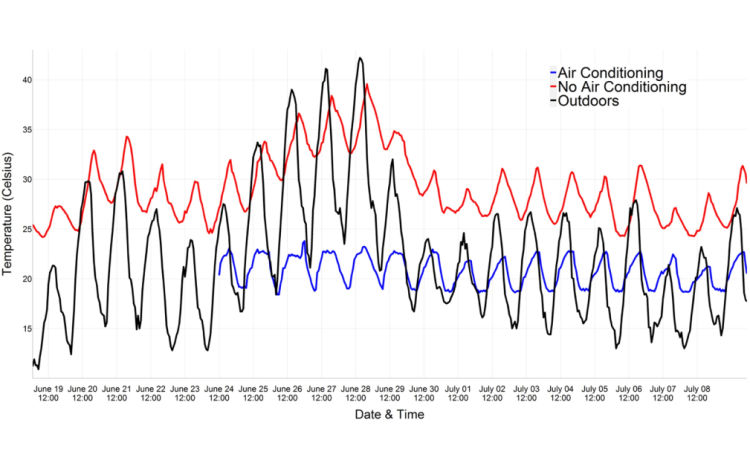

Dr. Henderson: We've used the data in quite a few different ways. First, we accessed data from areas affected by the heat dome and compared indoor temperatures in environments that we could tell did not have air conditioning with indoor environments that did. The comparisons really highlight how hot some of these environments can get without air conditioning. Being able to show people that information has been incredibly valuable.

Then we developed models that can tell us how hot it might get indoors depending on what's being observed and forecasted outdoors. This gives us some information about what might happen inside because of the temperature outside.

Based on the hot weather that we had this summer in BC, we’re looking at developing a network of indoor temperatures that we watch when it is hot outside to give us even better information.

When we have hot weather, we're getting regular reports from the ambulance service, 911, coroners, and emergency rooms across the province. Indoor temperature data from ecobee is another piece of information that we can use to understand the impacts of heat on the population.

ecobee Citizen: Your academic paper was released in February 2022. Do you know if there are any policy changes being implemented to avoid this kind of tragedy in the future?

Dr. Henderson: Yes. We’ve had huge policy changes in the past year. After that event, we formed a provincial committee to develop a BC Provincial Heat Alert and Response System (BC HARS). We had these systems in place in a few different places in the province prior to last year, but now we have set this out provincially and there are a couple of key features of this new policy.

First, it helps us to distinguish between a heat warning and an extreme heat emergency. A heat warning is when it is very hot compared with what we would expect at that time of year, but temperatures are staying stable, and that's what we experienced this summer. Late July was probably the longest stretch of extremely hot weather we've ever had in BC, but temperatures stayed stable the whole time versus the dangerous pattern of temperatures going up every day as we saw in the 2021 heat dome. And if we saw that pattern in the forecast, then we would issue an extreme heat emergency. That means we would use the emergency alert system to send text messages to everyone affected and to help them prepare.

The BC HARS also lays out roles, responsibilities, and recommendations for public health, for the ambulance service, and for municipalities under these two different conditions, so that agencies and municipalities can develop their own plans. The ecobee data also helped us develop the Extreme Heat Preparedness Guide. In the same way that we have guidance to help families prepare for an earthquake, now we have that guidance to help prepare for extreme heat with a strong focus on indoor temperatures. And if you know it gets very hot in your home, and you don't have access to air conditioning, then you need to take special precautions, like possibly going to stay with friends and family who have air conditioning.

The number one risk factor in extreme heat is low socioeconomic status.

ecobee Citizen: Who is most vulnerable to these types of extreme heat waves and heat domes?

Dr. Henderson: Mental illness, older age, disabilities, diabetes, and substance use disorder are important risk factors. There are many factors, but the number one risk factor in extreme heat is low socioeconomic status. The impacts are not uniform across the population, they are inequitable, and we see the deaths occur in communities where there's more deprivation.

There is real value in investing in urban greenery, especially in neighbourhoods with lower socioeconomic status.

ecobee Citizen: Any other risk factors you think are worth mentioning?

Dr. Henderson: We found that there was a protective effect based on how much tree canopy was in about 100 meters of a home. That protective effect was significant even in areas where we saw significant deprivation. That is telling us that tree canopy matters no matter where it is, and there is real value in investing in urban greenery, especially in neighbourhoods with lower socioeconomic status where people may not be able to afford air conditioning, and where there may not be concentrations of libraries or community centers where people can go cool off.

If we have a green canopy in those places, it will help to protect those populations. It can make several degrees of difference indoors, and we know risk really increases if you're living at sustained temperatures over 31°C degrees and you're a susceptible person. Healthy young people can usually tolerate those temperatures without too much risk, but for susceptible populations, those sustained temperatures over 31 are dangerous. If we can have more trees around and bring indoor temperatures down from 32 to 29 because of those trees, we will make a really big difference in terms of the human health risks.

If you can cover your windows from the outside, you're looking at 2-3°C difference in indoor temperatures.

ecobee Citizen: For people who don’t have air conditioning, and maybe can’t install it for various reasons, what else can they do besides going somewhere else that has air conditioning?

Dr. Henderson: A primary factor in extreme indoor temperatures is windows. There’s a process called solar heat gain through windows, and the quality of the window really matters. If you have single-pane windows, the solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) is very high. If you have double-paned windows, it's reduced. If you have double-paned windows with a reflective coating on one of the panes, it's reduced again.

If the sun never hits your window, you're in the best position possible. In many places, people have shutters over their windows on the outside. This is very common in hot Mediterranean environments, and the purpose of those shutters is to keep the sun off the windows, so you don't have that solar heat gain.

Any way that you can cover your windows from the outside, you're probably looking at a two-to-three-degree difference in indoor temperatures. Even just taping up mural paper or cardboard on the outside of your windows is going to make a difference.

Then there is what I would call clever management of the indoor environment. In the morning and afternoon, you want to close your blinds, curtains, or shutters and close everything up so that you're trapping cooler air indoors. And in the evening, when the temperatures may drop below 30, you should open everything up as much as possible and place fans by the windows so that they're blowing and pulling the cooler overnight air into the room.

The technology exists, but we just don't use it yet.

ecobee Citizen: What can landlords and homeowners, who may have more power to make structural changes, like installing air conditioning, do to help us avoid repeating this tragedy in the future?

Dr. Henderson: The Intact Centre for Climate Adaptation put out a guide recently on reducing the threats of extreme heat, so I would highly recommend homeowners, landlords, and building managers review that resource.

But I also want to reiterate that air conditioning is not the only solution to this problem. There are homes all over the world that do not have air conditioning. They are well adapted to the hot temperatures because it is hot there every year, but they also just build the environment to manage those hot temperatures.

I think we need to be looking at holistic ways to manage this heat. Mechanical cooling has a role to play, especially if we're looking at heat pumps and newer technologies to provide cooling. But ideally, we want to combine that with changing the built environment so that we're also reducing temperatures.

That can be as simple as:

-

Putting shutters or awnings over the windows to keep the blaring high sun out of the home.

-

Changing the windows in a building so that they have good thermal properties.

-

Ensuring roofing materials that reduce heat gain, such as green roofs, white roofs, or solar panels. Comparatively, asphalt roofs absorb heat.

I’ve talked to a lot of people about these solutions and the key message they always give me is that technology exists, but we just don't use it yet. We need to look at implementing these building policies more provincially and nationally that require, or at least incentivize, the use of these existing technologies.

The kind of data that ecobee can provide is going to be invaluable as we look to adapt to these hotter conditions.

ecobee Citizen: Absolutely. It’s quite clear why this research is important, but is there anything else you want to add about the importance of the research or the effects of climate change that we're seeing?

Dr. Henderson: I'll just say that we've now had two unprecedented hot weather events in BC in the past two years. In 2021, we had this event where we had higher temperatures than we'd ever observed before and higher temperatures, honestly, than we thought we could observe in this region. We may have expected events like that in 2050, but not in 2021. And then we've just come through a very hot weather event, not nearly as hot in terms of temperature, but it lasted a long time for this region. This is a temperate climate, so we’ve never had temperatures in the 30s for a week.

From my perspective, what the climate is telling us is that this is life now. We can't hope that these events are a one-off. We must adapt to them, so how do we accelerate that adaptation? And an important part of that will be addressing the question of indoor overheating.

First, we must stop building buildings that get so hot that people can die in them. We now have evidence that people die indoors when it gets too hot. Anything new that gets built needs to be resilient to high outdoor temperatures.

Second, what do we do with existing buildings? What do we do with buildings that were built 10 years ago and don't have air conditioning, but aren’t going to be replaced for another 50 or 60 years? What are the retrofit options? So much research is needed at that nexus of when we modify a building, how does it affect indoor temperatures? And the only way that we can do that research is with measurement. The kind of data that ecobee can provide, and the kind of data that Internet-connected devices can provide, is going to be invaluable as we look at how we're going to adapt to these conditions.

We need to start moving away from glass buildings, for example, and into more passive buildings where we can combine the design of the building with the opportunity for mechanical cooling, so that we achieve a better indoor environment with minimal energy use and still maximal aesthetics.

We must do it, and it may take the government saying you can't build a glass tower anymore; it’s not allowed and it’s not okay in this climate.

ecobee Citizen: Thank you for this. Anything else you want to add?

Dr. Henderson: The final thing I will add is that nobody questions that it needs to be warm inside in the winter. You wouldn't be able to have a home that is 10°C in the winter. If it was −20°C outside, we know that the home should be at least 18°C. We must apply the same logic at the other end of the spectrum. Currently, we view cooling, and having an adequately cool indoor environment, as a luxury. We don't see heating as a luxury. We see it as being a necessity for human life, so we need to start bookending the range of indoor temperature with the same kind of logic at both ends.

Interested in joining over 200,000 ecobee customers and helping scientists like Dr. Henderson design the sustainable homes and communities of the future? Sign up for Donate Your Data in a few short steps:

-

Open the ecobee app.

-

Tap the Account icon in the top-left corner.

-

Select Donate Your Data.

-

Toggle on Donate Thermostat Data.

-

Learn how your data is anonymized and privacy protected, then tap Accept & Join.

About Dr. Henderson

Dr. Sarah Henderson is the Scientific Director of Environmental Health Services at the BC Centre for Disease Control, and Scientific Director of the National Collaboration Centre for Environmental Health. She oversees a broad program of applied research, surveillance, and knowledge translation to support evidence-based environmental health policy and practice in BC and across Canada. Dr. Henderson loves big data, environmental public health, and helping stakeholders get the answers they need.

Did you enjoy this article?

Thanks for letting us know!